Weinstein Company Announces Asian Film Fund

August 8, 2007

Apprehensive. . . I suppose that is the best way to describe my immediate reaction to the recent announcement that the Weinstein Brothers have launched a $285 million fund to invest in Asian film. (Here’s a link to the announcement for more details.)

Undoubtedly, it is thanks to folks like the Weinsteins and Quentin Tarentino (who is also heavily involved with this project) that Western audiences have had access to so many of the great Asian films that have come out in recent years. I have loved these films and should just be happy that several new similarly-themed films will be making their way into the pipeline.

On the other hand, a very large part of why I like foreign films – beyond the rather obvious reason that they offer a glimpse at other cultures – is that they are so not Hollywood, for lack of a better way to express it. Much as people flock to indie films for the same reason, these films offer different perspectives than those normally offered in the mainstream American releases. Thus, it must give one pause when an annoucement like this one comes out, particularly when they’re saying that part of the intent of the new venture will be to add a “Western sensibility” to these Asian-themed films. Even though so much of the Weinsteins’ work with Miramax over the years demonstrated that they are not afraid of taking chances and going against the norm, it still makes one nervous to see that the rumored film possibilities being explored include a remake of the Kurosawa classic Seven Samurai and a live action version of Mulan, and that many actors being rumored to be involved include several notable non-Asian actors (I saw George Clooney’s name floating around in one article).

And so, while happy to see Asian cinema getting some of its much deserved recognition and that some more great films in the same vein might soon be coming out, this whole project does somewhat resemble mere exploitation of existing ideas by a Hollywood struggling to come up with its own original thoughts. With the talented names involved in these films, hopefully the results will be good. I just think it’s too early to tell and that there are certainly some reasons for concern.

Cinema Paradiso (The New Version, 1988)

July 17, 2007

When Giuseppe Tornatore’s 1988 film Cinema Paradiso came out, it was one of those foreign films that comes along every now and then that actually manages to get some attention from those audience members usually scared off by subtitles. The attention was well warranted. In my opinion, it’s one of the most moving and heartfelt films to come out in the last 20 years.

A few years ago, I was given the DVD version of the film for Christmas. It contains not only the well-known theatrical release of the film, but also the newly mastered “New Version,” incorporating about 50 minutes of additional footage that Tornatore originally intended to be included in the film. As is often the case, studio execs had balked at the idea of a nearly three-hour long film and thus the footage had been cut for theatres.

I am not really a fan of director’s cuts. While I respect the director’s view and think they can rightfully claim some provenance over their films, I also respect good film editors and think they usually tend to make good choices in their cuts.  On the other hand, I do think the commercial pressure put on film-makers can often lead to questionable compromises. The lack of faith in an audience’s attention span definitely can lead to some poor decisions – the classic example being the excessive editing of Orson Welles’s Magnificent Ambersons, which took place while the director was off filming in Brazil. To his dying day, Welles insists that these cuts ruined his vision for the film, and finding the director’s cut of this film remains the elusive – and rather unlikely – holy grail of the film world.

On the other hand, I do think the commercial pressure put on film-makers can often lead to questionable compromises. The lack of faith in an audience’s attention span definitely can lead to some poor decisions – the classic example being the excessive editing of Orson Welles’s Magnificent Ambersons, which took place while the director was off filming in Brazil. To his dying day, Welles insists that these cuts ruined his vision for the film, and finding the director’s cut of this film remains the elusive – and rather unlikely – holy grail of the film world.

Being a big fan of Giuseppe Tornatore’s film, I held out for some time on watching the new version, suspecting that all that extra footage would just water down the film’s undeniable emotional punch. Fast forward to the past week, however, when I finally decided it was time to give this new version a shot, thinking that maybe a scene or two of the deleted footage might at least be interesting. I wasn’t trying to be pessimistic – just realistic. I mean, why mess with a film that’s already that good? Imagine my surprise when I discovered that not only did the extra footage not ruin the film, it actually made a great film even better.

Both versions of the film are more or less the same for the majority of the film. The film begins showing film-maker Salvatore di Vita returning to his apartment in Rome one night to discover that his mother had called during his abscence. Her message informs him that his boyhood mentor and friend Alfredo (played in the film by Philipe Noiret in one of his most famous roles) had just passed away in his hometown and the funeral would be held the next day. Most of the film is subsequently a flashback to Salvatore’s boyhood and his growing up under Alfredo’s tutelage and learning about life, love, and film. The biggest difference in the two versions comes when Salvatore arrives in his hometown for the funeral. At this point, the theatrical version closes relatively quickly, only lasting another 15 or 20 minutes or so. It focuses almost exclusively on Salvatore’s coming to terms with the loss of Alfredo and the old movie theatre, which is torn down while he is there. In the new version, on the other hand, Salvatore’s return last nearly a third of the film’s total running time, and the additional footage shows him facing additional aspects of his past, including his first true love, his family, and his changing hometown. This broadened view, in my opinion, makes much more sense with the rest of the film and makes it more cohesive as a whole.  For one thing, it resolves many of the questions the theatrical version left unanswered concerning Salvatore’s romance with Elena (and believe me, if you were a fan of the couple’s moving romance in the original version, you will want to see how it gets wrapped up in the extended version). Further, the additional footage extends some of the wider themes introduced earlier in the film, and as a result, the film is not just a memorial for Salvatore’s lost friendship (as it more or less is in the theatrical version), it’s an elegy for his entire past – an eloquent portrait of why some of us can never stop being haunted and influenced by our childhood.

For one thing, it resolves many of the questions the theatrical version left unanswered concerning Salvatore’s romance with Elena (and believe me, if you were a fan of the couple’s moving romance in the original version, you will want to see how it gets wrapped up in the extended version). Further, the additional footage extends some of the wider themes introduced earlier in the film, and as a result, the film is not just a memorial for Salvatore’s lost friendship (as it more or less is in the theatrical version), it’s an elegy for his entire past – an eloquent portrait of why some of us can never stop being haunted and influenced by our childhood.

I suppose you can say it is a very rare experience indeed to get to see a film twice for the first time. And yet, thanks to this new version, I feel like I had just such an experience with Cinema Paradiso. I was blown away by the sincerity and artistry of the film the first time through. Then, seeing it again with all the new footage, I was blown away once again. If you’re like me – reluctant to see director’s cuts and skeptical that the additional footage is actually worth salvaging – you should check out the extended version of Cinema Paradiso. It just might change your mind.

Kontroll (2003)

May 18, 2007

Kontroll is an interesting, offbeat film by Hungarian director Nimrod Antal. As with most interesting, offbeat films, I’m somewhat reluctant to recommend it outright, since such films often are more polarizing ones that will either resonate with you meaningfully or else just bore you to tears.  I have a feeling, however, that Kontroll probably hits more than it misses. It may not be a perfect film, and I imagine it might start to drag in parts if I watched it a second time – but it does seem to have something for everybody. In fact, it can equally be considered comedy, action, or drama. It’s a funny, entertaining, stylish film that also tackles some very serious questions.

I have a feeling, however, that Kontroll probably hits more than it misses. It may not be a perfect film, and I imagine it might start to drag in parts if I watched it a second time – but it does seem to have something for everybody. In fact, it can equally be considered comedy, action, or drama. It’s a funny, entertaining, stylish film that also tackles some very serious questions.

Earlier this year, I mentioned that Cache made me aware that perhaps I should be paying more attention to some of the films coming out of film festivals like Cannes. (The festival’s going on now, by the way, and celebrating its 60th anniversary. I was excited to see that this year’s festival was opening with a film called Blueberry Nights by Chinese director Kar Wai Wong [of In the Mood for Love fame]; I was a little less excited when I saw the film starred Norah Jones and Jude Law, but I guess the guy knows what he’s doing.) Kontroll reinforced this notion with me. With the sheer number of quality international films coming out these days, it can be hard to know which ones are worth checking out, but keeping up with the buzz coming out of these festivals is a good place to start.

All of Kontroll takes place underground in Budapest’s metro system. I have always thought that the elaborate subterranean systems of subways make great settings for film – an appropriate location for any film dealing with what lies beneath a society, all its repressed fears, worries, hopes, etc. – and yet I’m still waiting for the consumate underground film. (For a recent example of how not to do such a film, check out Takashi Shimizu’s low budget J-horror film Marebito. Actually, don’t check it out . . . or if you do, do so only with low expecations.) Kontroll may not be the film I’ve been waiting for, but it certainly does play with those themes.  The main character, Bulcsu (Sandor Csanyi), seems to be going through an existential crisis. Working as a ticket inspector during the day, Bulcsu refuses to leave the station even at night, as he struggles to understand through the microcosm of the subway the meaning of life, justice, work, and love. The story of Bulcsu and his team searching through the tunnels for a man pushing innocent victims in front of trains is exciting, humorous, and fast-paced. The script is a little rough, and I don’t always relate with the characters or their motivations. Overall, however, I’d say that this film’s strengths largely outweigh its weakenesses and that the film is worthy of a viewing.

The main character, Bulcsu (Sandor Csanyi), seems to be going through an existential crisis. Working as a ticket inspector during the day, Bulcsu refuses to leave the station even at night, as he struggles to understand through the microcosm of the subway the meaning of life, justice, work, and love. The story of Bulcsu and his team searching through the tunnels for a man pushing innocent victims in front of trains is exciting, humorous, and fast-paced. The script is a little rough, and I don’t always relate with the characters or their motivations. Overall, however, I’d say that this film’s strengths largely outweigh its weakenesses and that the film is worthy of a viewing.

Hungary is not a country particularly well known for its cinematic tradition. In fact, I’m not sure, but I believe this might have been the first Hungarian film I had ever seen. I know it was the first film from Hungary to be shown at Cannes in 20 years. The film has a central/eastern European feel about it. Its humor is very visceral, and the scenery and actors in it have a bleak quality about them – even during the film’s more energetic and fun parts. Yet, I’d rate my first Hungarian film experience a positive one and hope that it’s a sign of more things to come (although it looks like the success of Kontroll has resulted in Hollywood stealing Antal away from his home country for the time being).

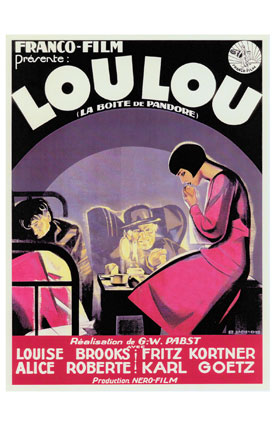

Pandora’s Box (1929)

March 30, 2007

I guess it must have been a Louise Brooks documentary that I saw on TV or something,  but for a few years now, I have been anxious to see Pandora’s Box (Die Buchse der Pandora). Unfortunately, even though it is considered one of Brooks’ crowning achievements and a classic of the silent era, this is not a film that’s readily available at your neighborhood library or video store. Thus, it wasn’t until recently, with the release of the Criterion Collection edition this past November, that I finally had access to a copy of it. Earlier this month, I received a copy through Netflix and at last had a chance to see it. The verdict? It was well worth the wait.

but for a few years now, I have been anxious to see Pandora’s Box (Die Buchse der Pandora). Unfortunately, even though it is considered one of Brooks’ crowning achievements and a classic of the silent era, this is not a film that’s readily available at your neighborhood library or video store. Thus, it wasn’t until recently, with the release of the Criterion Collection edition this past November, that I finally had access to a copy of it. Earlier this month, I received a copy through Netflix and at last had a chance to see it. The verdict? It was well worth the wait.

These days I imagine silent films are more of an acquired taste. With that in mind, if you have not seen a silent film before, you might want to check another one out first before diving into Pandora’s Box, which – at over two hours long – is a rather lengthy silent era piece. On the other hand, if you like silent films and Louise Brooks in particular (by the way, Greenbriar Pictures Show did a really well-done post on Brooks a few months ago that you can find here), then you will likely enjoy this film. The story describes the freespirited Lulu (Brooks) whose beauty incites jealousy in her many admirers which leads, in turn, to her ultimate downward spiral. It’s one of those great gems of early film that demonstrates the medium when it still seemed overly ambitious in its literary intents. It also is still early enough in the twentieth century that it still strongly resembles its Victorian forebears, as the basic plot and most of the cast seems to come straight out of a Dickens novel. Lulu herself in many ways resembles Thackeray’s Becky Sharp in the manner in which she is portrayed as simultaneously repugnant and entrancing, confining and liberating  (in many ways, Brooks herself was viewed in such contradictory terms). The film seems to hover between the Victorians’ conventional moral stand and a more forward-looking feminist view, and it’s interesting to note that this film contains one of the cinema’s first (if not the first) lesbian character in Countess Anna.

(in many ways, Brooks herself was viewed in such contradictory terms). The film seems to hover between the Victorians’ conventional moral stand and a more forward-looking feminist view, and it’s interesting to note that this film contains one of the cinema’s first (if not the first) lesbian character in Countess Anna.

Director G. W. Pabst, one of those remarkably influential German directors of early film history, does a splendid job with the film and uses some surprisingly innovative shots. Brooks, as always, is entrancing. The story, while somewhat predictable, is nonetheless engaging. Criterion’s release of the film is of the highest quality and includes a few different styles of accompanying scores. (Apparently, there is a second DVD included in the release that has all sorts of special features.) Overall, I enjoyed this DVD very much and recommend it highly to any fan of silent films.

Some closing thoughts on French film

March 26, 2007

I know it’s rather foolish to try and make generalizations about a whole nation’s film tradition based solely on a handful of films – particularly when it is a tradition as rich and diverse as France’s. However, these last several weeks have been the most prolonged exposure I have had to French film – having watched seven films, both classic and modern, from a variety of genres (although I seemed to shortshift comedy – a genre it seems the French would probably be pretty good at). Thus, limited as they may be, I thought it would be appropriate to conclude with a few closing thoughts before moving on.

When I first started reviewing these films with Band of Outsiders, I compared French film to lyric poetry – shunning traditional narratives and realistic portrayals in favor of cinematic devices that could more appropriately convey inner emotions and development. Having seen several more French films now, I still believe this to be the case. In fact, the only films I reviewed where this wasn’t the case were The Sorry and the Pity, which was a documentary, and The Rules of the Game, which was a pre-New Wave film from an era where the French cinema was still struggling to develop its own identity. Even a film such as Cache, which on the surface is merely a thriller, delves deep into the soul of its protaganist and paints a complex psychological portrait of how we are shaped by childhood, love, politics, and many other factors. More than anything else, it is the artistry with which French films paint such inner landscapes that I think sets it apart from other nations’ film traditions. It’s this impulse that seems to compel the French to make so many arthouse style films – the kind that one describes, depending on his or her take, as either “beaufully rendered” or “snooty.”

As is so often the case, an increased exposure to something leads to a greater appreciation of it. And while I still wouldn’t say that French films are among my favorite foreign films, I must say that having watched all these films over these past several weeks I have a much greater respect for the French cinematic tradition. Not only can this tradition hearken back to a shining past that has produced some truly classic films, particularly during the New Wave era, but judging from the quality of some of the films that have come out of France in recent years, it looks like the future of French film is destined to be bright as well.

The Rules of the Game (1939)

March 23, 2007

As might be evident from the near month that has passed since my last post, my schedule has been quite busy. I was hoping to wrap up my little series on French film before we left for Paris, but – mon Dieu! – such an idea proved quite a bit too ambitious. Thus, I now have a backlog of a few posts that I’m hoping to get to in the next couple of weeks, so all you rabid classic and foreign film fanatics can simmer down . . .

The last French film I saw before our trip was Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game (La regle du jeu). It’s considered a classic of French film and nearly everything I had ever read about it  describes it in good to glowing terms, so I was rather surprised when I didn’t like it much at all. The basic plot follows a group of French bourgeois who gather at a country chateau for a party. While most of the film has a flippant feel to it – merely following the back-and-forth amorous exploits of the various characters – as the night’s events unfold, it becomes clear that the various, seemingly meaningless entanglements can lead to rather serious consequences. This is certainly a worthwhile plotline that’s been used in many great pieces of art. It’s just that Renoir’s work seemed to be lacking something. It was like a screwball comedy without the comedy, or maybe like a Mozart opera without the beautiful music.

describes it in good to glowing terms, so I was rather surprised when I didn’t like it much at all. The basic plot follows a group of French bourgeois who gather at a country chateau for a party. While most of the film has a flippant feel to it – merely following the back-and-forth amorous exploits of the various characters – as the night’s events unfold, it becomes clear that the various, seemingly meaningless entanglements can lead to rather serious consequences. This is certainly a worthwhile plotline that’s been used in many great pieces of art. It’s just that Renoir’s work seemed to be lacking something. It was like a screwball comedy without the comedy, or maybe like a Mozart opera without the beautiful music.

Doubtless, the film seems to be a trailblazing one. One can find traces of its influence, for example, in some of the great films Fellini and Antonioni did in the early 60s. These later Italian films, however, were to me much more heartfelt and mature. Perhaps it was because I had seen these later, better done treatments of the same themes that I did not fully appreciate Renoir’s film. While I understood and admired the intents of The Rules of the Game, I just couldn’t get drawn into it, and only a few minutes into the film, I already found myself wondering how much longer I had to go.

One final note worth mentioning. This is the only pre-New Wave French film I reviewed in the past several weeks. With that in mind, this film is a good example of what the New Wave movement was rebelling against. The movement’s leaders, like Godard and Truffaut, were frustrated with the stale conventions and recycled plotlines of classical French cinema and wished to reinvigorate the artform and explore the unique creative possibilities offered by the big screen. Watching a film such as The Rules of the Game and then comparing it to something like Band of Outsiders is a good way of seeing just how revolutionary the New Wave movement truly was.

The Sorrow and the Pity (1969)

February 27, 2007

I know that not everybody likes documentaries. In particular, not everybody likes four-hour long documentaries spanning two DVDs. And yet, for those people interested in history, I would highly recommend The Sorrow and the Pity (Le Chagrin et la Pitie). This sprawling work (it’s worth noting that even though it’s on two discs, Netflix considers both discs to be one film and sends them both simultaneously) paints a highly informative, moving portrait of life in occupied France during WWII. No doubt about it, the film is long.  Furthermore, to somebody like myself who doesn’t know much about the history of occupied France, there were some portions describing incidents I had never heard of where I found myself quite lost (this was particularly true of the first disc). Yet, these are the only possible shortcomings I can think of. Filmmaker Marcel Ophuls masterfully interweaves archival footage with retrospective interviews to create a historic piece that truly brings the past to life. The resulting, complex tapestry of viewpoints (Ophuls interviews former aristocrats, working people, German soldiers, French Resistance fighters, pro-German French citizens, policymakers, you name it) is as revealing as it is comprehensive.

Furthermore, to somebody like myself who doesn’t know much about the history of occupied France, there were some portions describing incidents I had never heard of where I found myself quite lost (this was particularly true of the first disc). Yet, these are the only possible shortcomings I can think of. Filmmaker Marcel Ophuls masterfully interweaves archival footage with retrospective interviews to create a historic piece that truly brings the past to life. The resulting, complex tapestry of viewpoints (Ophuls interviews former aristocrats, working people, German soldiers, French Resistance fighters, pro-German French citizens, policymakers, you name it) is as revealing as it is comprehensive.

My first reaction to the film was mainly just surprise. When I think of France during WWII, I typically think of the Resistance fighters – brave, daring patriots like those so often portrayed in 40s era films like Casablanca. The reality, however, was of course quite a bit more complex, as the documentary shows that there was actually a fair amount of pro-German sentiment (along with its accompanying anti-Semitism) in France during the War, particularly during the early years. France was actually the only occupied country that participated in a cooperative program with Germany, sending commuting workers over the border in work-programs, passing cooperative laws, etc. Even as the War progressed and the Resistance movement picked up, there were still many people in France who were either apathetic or even welcoming to the German occupation, including many people who turned in known Resistance fighters. Despite the fact that this was not an uncommon reaction, there nonetheless was a widespread, violent backlash by the French against suspected German sympathizers once the War was over. In fact, it is stories describing this backlash of French against their own countrymen (rather than those tales describing the earlier acts of occupying German soldiers) that are the most ghastly in the film.

In all the hours of interviews, it’s interesting that those being interviewed some 25 years or so after the fact by and large seem rather calm and detached from the events they are remembering. And yet, ironically, it’s this detachment that gives the documentary its emotional punch. After hearing these level-headed people so calmly describing such horrific events from their past, it slowly sinks in that so many lives were affected by a war waged not by people, so much, as ideologies. Hearing first-hand accounts of everyday people getting swept up in ideological fervor – movements that they would later regret participating in – is sobering. It’s the main strength of The Sorrow and the Pity. It makes one realize that so many people were caught up in something much bigger than themselves. And, in turn, the film simultaneously makes these much-bigger ideologies suddenly appear not so big and important at all, once one compares them to all the lives that were turned upside down and wasted as a result.

its emotional punch. After hearing these level-headed people so calmly describing such horrific events from their past, it slowly sinks in that so many lives were affected by a war waged not by people, so much, as ideologies. Hearing first-hand accounts of everyday people getting swept up in ideological fervor – movements that they would later regret participating in – is sobering. It’s the main strength of The Sorrow and the Pity. It makes one realize that so many people were caught up in something much bigger than themselves. And, in turn, the film simultaneously makes these much-bigger ideologies suddenly appear not so big and important at all, once one compares them to all the lives that were turned upside down and wasted as a result.

Blue (1993)

February 20, 2007

Most of the people I’ve either read or heard discussing this film tended to really like it, which means I’m going to be expressing a minority opinion here, because I was only lukewarm in my reaction. Blue (or in its original French, Bleu) is part of Krystof  Kieslowski’s Three Colors (Trois couleurs) trilogy. I suppose since it’s in French and takes place in France, it’s considered a French film, although Kieslowski is actually a Polish filmmaker, which explains in part why there seems to be a East European feel about it (although that probably has just as much to do with the film’s bleak subject matter). Each film in the trilogy is titled after a different color in the French flag and represents a different ideal of the French motto “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity.” Blue deals with the first ideal, liberty.

Kieslowski’s Three Colors (Trois couleurs) trilogy. I suppose since it’s in French and takes place in France, it’s considered a French film, although Kieslowski is actually a Polish filmmaker, which explains in part why there seems to be a East European feel about it (although that probably has just as much to do with the film’s bleak subject matter). Each film in the trilogy is titled after a different color in the French flag and represents a different ideal of the French motto “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity.” Blue deals with the first ideal, liberty.

Juliette Binoche plays the main character, Julie Vignon. After a car accident kills both her husband and her daughter, Julie seemingly has nothing to live for. Failing in a suicide attempt, she proceeds to commit something akin to a symbolic suicide instead – getting rid of all her belongings, moving to an anonymous location without notifying any friends or relatives, and generally detaching herself emotionally from events around her. Soon, however, a series of occurrences begins to pull her out of her withdrawal and to reattach her with some of those former associations she tried so hard to escape.

Liberty is a tricky concept in the film. Superficially, Julie does not seem to obtain the liberty she seeks, since she is still bound up in the old associations she originally wanted to forget. And yet, Julie’s passage to self-discovery opens the door for her to be able to live a life of emotional fullness – something she thought impossible following the death of her family. In fact, the piece of symphonic music that her husband (though it debatedbly may be Julie herself who is the composer) left unfinished is commonly interpreted as symbolic of Julie herself. Thus, only when she has learned more about herself and freed herself from her self-imposed restrictions can any attempts be made to bring this piece of music to completion.

As sometimes happens, the more I’m thinking and writing about the film, the more I’m starting to warm up to it, but the fact is that I was pretty bored while watching Blue. Granted, it’s a film dealing with psychological development and inner emotions –  something that isn’t always riveting on the screen – but those are actually the type of films I typically enjoy. I just don’t think this particular one was all that interesting. Even Binoche’s talents, which I appreciate, couldn’t save this film for me. It was almost as if Binoche did such a good job acting detached and emotionless that I couldn’t find any ground to empathize with her and subsequently felt detached from the film itself (how’s that for a backhanded compliment?). I suppose there was enough intriguing material in this film that I might try going forward in this trilogy, but I just haven’t made up my mind yet. The opening installment certainly hasn’t sucked me in.

something that isn’t always riveting on the screen – but those are actually the type of films I typically enjoy. I just don’t think this particular one was all that interesting. Even Binoche’s talents, which I appreciate, couldn’t save this film for me. It was almost as if Binoche did such a good job acting detached and emotionless that I couldn’t find any ground to empathize with her and subsequently felt detached from the film itself (how’s that for a backhanded compliment?). I suppose there was enough intriguing material in this film that I might try going forward in this trilogy, but I just haven’t made up my mind yet. The opening installment certainly hasn’t sucked me in.

Hiroshima, mon amour (1959)

February 16, 2007

Hiroshima, mon amour will certainly not be everyone’s cup of tea. It’s an extremely serious, nontraditional film – the type of challenging arthouse offering that one could conceivably see SNL spoofing (if it weren’t for the fact that it deals with such undeniably serious themes that such a spoof would be considered quite insensitive). The first 15 minutes of the film is essentially a visual lyric poem, with opaque, rhythmical dialogue voiced-over a montage of accompanying images of the bombing of Hiroshima. Many a Joe Somebody probably loses interest in this opening sequence and doesn’t even make it to where the film lapses into its narrative form, dealing with the story of a French actress visiting Hiroshima and having an affair with a Japanese man.  Not that the film becomes any less challenging at this point. Indeed, the couple’s relationship and their stilted conversations are heavy with symbolism representative of humanity’s post-WWII burden.

Not that the film becomes any less challenging at this point. Indeed, the couple’s relationship and their stilted conversations are heavy with symbolism representative of humanity’s post-WWII burden.

Comparing the film to poetry is appropriate, as the work seems very much like the verse of many modern poets – it’s either going to resonate with an individual or it’s not. Thus, while I can certainly understand why many people will rave about this film, I personally liked it, but wasn’t rolled over by it. I liked its basic concept, found many of the scenes to be quite touching, and thought it was well crafted overall. It just seemed to be operating on a slightly different aesthetic wavelength or something, as I suppose sometimes happens.

Perhaps its most accurate to say I liked the premise of the film and what it was trying to accomplish; I was just somewhat disappointed by the particulars of how it was executed. The film’s themes are certainly impressive, dealing with the catastrophic events one faces in life – whether in love or war – and that essential human need to forget and move on following such events. It’s not that simple, however, as there’s also an elemental need to remember those influences that shaped us, and it’s in this conflict between remembering and moving on that the man and woman now find themselves torn apart. The couple’s stories are obviously supposed to be syptomatic of larger historical and social trends, which perhaps explains why I thought the dialogue was a bit too abstract and impersonal. It seems as if the film removes some of the genuineness of their relationship in order to serve loftier artistic goals. And yet, even with that said, well done treatments of such themes are typically worth checking out. So while the film did not really strike the right chord with me, I know it has done so with others – thus if it sounds like the kind of film you typically enjoy, you should probably go ahead and give it a chance.

Cache (2005)

February 8, 2007

I’ve never been one to keep up with the latest news coming out of all the major film festivals – even though many of them seem to specialize in the arthouse and foreign lines of film that are right up my alley.  Thus, I had never heard of the 2005 French film Cache (sometimes translated to “Hidden” in English, sometimes not), which evidently won quite a bit of acclaim at that year’s Cannes Film Festival. Nor had I ever heard of the film’s director, Michael Haneke, even though he won the festival’s best director award for the film and is a regular at Cannes with a series of laudable festival entries. I’m beginning, however, to think maybe I should pay more attention to Cannes and similar festivals, as Cache was just the kind of intelligent, well-crafted, and original film that I enjoy seeing.

Thus, I had never heard of the 2005 French film Cache (sometimes translated to “Hidden” in English, sometimes not), which evidently won quite a bit of acclaim at that year’s Cannes Film Festival. Nor had I ever heard of the film’s director, Michael Haneke, even though he won the festival’s best director award for the film and is a regular at Cannes with a series of laudable festival entries. I’m beginning, however, to think maybe I should pay more attention to Cannes and similar festivals, as Cache was just the kind of intelligent, well-crafted, and original film that I enjoy seeing.

I’ve typically discovered that when a film is described as a “taut psychological drama,” it means little more than “the main character is slightly unbalanced and probably wants to kill somebody.” Such is not the case with Cache, which does much more justice to the phrase, demonstrating the potential complexity and longevity of our unresolved psychological issues. The “issues” Georges Laurent (played by Daniel Auteuil) is dealing with are not two-dimensional affairs, but rather, are the textured, mature problems of a man suffering from a wide range of troubles – everything from a childlike need for a parent’s love to more sophisticated adult political biases. Thus, when a stalker terrorizes Georges and his wife Anne (Juliette Binoche) with videotapes, phone calls, and mail that force him to confront his past both figuratively and literally, the resulting tolls taken both on Georges and on his relationships with those around him seem frighteningly realistic. Indeed, the realism of the film is one of its primary strengths.

Other than the always talented and alluring Binoche, the cast will likely be unfamiliar to  American audiences, although it is a very good one from top to bottom. Haneke’s direction is also superb, although it might try some people’s patience. It’s the kind of direction that you’ll either love or hate; it will either hypnotize you or make you turn the DVD off in frustration. This film certainly is not universal in its appeal, and I’m guessing it’s one where even its fans probably don’t enjoy watching it over and over again. It is, however, an inventive film, and its careful craftsmanship and stark, unsettling realism will likely strike a haunting chord with many attentive viewers.

American audiences, although it is a very good one from top to bottom. Haneke’s direction is also superb, although it might try some people’s patience. It’s the kind of direction that you’ll either love or hate; it will either hypnotize you or make you turn the DVD off in frustration. This film certainly is not universal in its appeal, and I’m guessing it’s one where even its fans probably don’t enjoy watching it over and over again. It is, however, an inventive film, and its careful craftsmanship and stark, unsettling realism will likely strike a haunting chord with many attentive viewers.